Just about every holidaymaker who goes sightseeing in Malta visits the famous Parish Church of St Mary in the town of Mosta. Its beautiful Rotunda, the third largest in the world, stands like a beacon dominating the skyline towards the north of the Island. As visitors stand in awe underneath the magnificent dome, they hear a story from the darkest hours of World War 2.

Mosta was in the direct flight path of enemy bombers retreating from or heading to the RAF base at Ta Qali. As a result the town was heavily bombed in the first four months of 1942, and civilian casualties were high. Never before had their faith been more important to the people of Mosta.

At 1640 hours on 9 April 1942, up to 300 of them were gathered in the church to hear Mass when a 500kg Luftwaffe bomb pierced the dome and landed among them. It failed to explode. The shocked parishioners were ushered out of the Church to safety and no-one was hurt.

News of the remarkable escape spread quickly across the Island, and among these deeply religious people it wasn’t long before the event was being described as a miracle. When the siege was over, the Maltese began to rebuild their lives and tried to forget the horrors of the war. But the story of ‘the Miracle of Mosta’ was kept alive, as a symbol of the faith and hope of the Maltese in such troubled times. In due course, a commemorative display was set up in an ante-room, with gift shop.

Inevitably, like many remarkable tales that are told and retold, over the years the tale of Mosta has reached mythical proportions, with the inevitable blurring of truth and fiction. A thorough investigation of all aspects of the event was carried out by the late Anthony Camilleri, published in his 1992 book ‘Il-Hbit mill-Ajru fuq ir-Rotunda tal-Mosta’. However, even he was at the mercy of the effect time has on the memory.

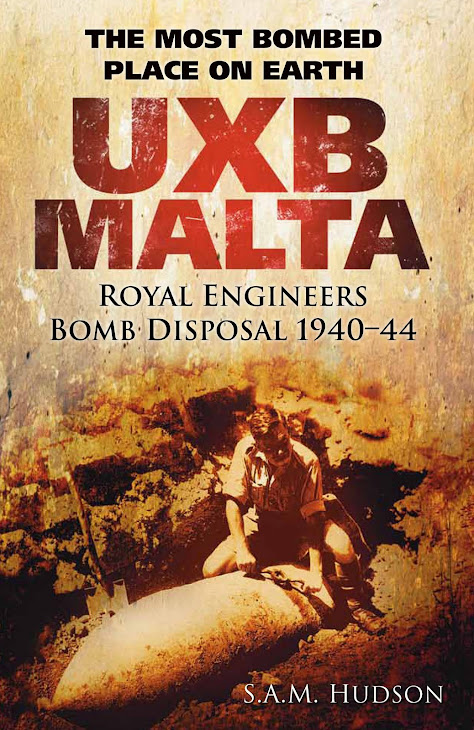

The photograph (see image R)

For many years this photograph was believed to show the actual unexploded bomb removed from the church at Mosta, and was sold in the church on that basis. The bomb shown here is at least 1000kg.

The bomb

The UXB removed from the church on 9 April 1942 was a 500kg German high explosive. Contrary to some recent claims, it was a live bomb; it was not full of sand and did not contain a message of greeting. The bomb on display in the church is not the real one but a similar example.

The removal

The emotional attachment to Malta of many who served there during World War 2 has drawn them to return as holidaymakers in recent decades. They often identify strongly with Mosta, so much so that some believe they were present that day in 1942. According to several sources in Malta, former RAF and Army servicemen from a range of regiments have stated that they shepherded the congregation out to safety, others that they picked up the bomb and carried it out of the church.

Who did it

The disposal of the unexploded bomb at Mosta on 9 April 1942 is logged in the official War Diary of the Royal Engineers Bomb Disposal Sections. For them, arriving after people had been led out of the church by their priests, there was no sense of a miracle at the time – it was just a routine UXB.

The bomb on display in the church represents something beyond the ‘miracle of Mosta’. It stands for just one of over 7000 unexploded bombs dealt with by the RE Bomb Disposal Sections in two years. The real story of the men who dealt with the Mosta bomb is uncovered in my book ‘UXB Malta’ available from 1st May 2010.

Wednesday 24 March 2010

Friday 19 March 2010

UXB Malta: making history

A whole year on from my first attempt to find the records of Royal Engineers Bomb Disposal in Malta, I finally held in my hands the relevant War Diary. In my elation, I could never have envisaged the task ahead of me.

A War Diary is a daily log of the main events of each relevant unit. The Diary of the Fortress Engineers, Malta, describes work done by the various subsidiary Companies, as well as air raids, casualties and damage to their headquarters. The Bomb Disposal (BD) Report for each week was attached as an appendix to the War Diary.

The first document I saw with the signature of 'Lt Geo D Carroll' as Bomb Disposal Officer was the BD Report for the week ending 10 May 1941. It listed the 59 unexploded bombs dealt with that week, with details for each one: serial number and date of the UXB report, the location, nationality, size and type of bomb (eg 50kg SD), whether it was on the surface or how deep it was buried. The final column logged the date the bomb was rendered harmless, with a brief description of the action taken.

It was only then that the enormity of what I'd uncovered began to sink in. As I read page after page describing what had actually gone on compared to what I’d found in books, I realised that the ‘booklet’ I'd planned to write couldn't possibly do the story justice. I began to contemplate writing my first book.

I had unearthed a goldmine: detailed, day to day account of the actions of RE Bomb Disposal in Malta from 1940 to 1944, and of the environment they worked in. More than a thousand pages of information revealed endless air raids, and the resulting thousands of unexploded bombs that were dealt with. Thanks to the National Archives, I was allowed to take copies of the documents, so I could study them at home between return visits to collect more.

But now I had to work out what all this information could tell me; statistics and lists are meaningless without interpretation. I was used to handling research material in some detail but this was on a different scale altogether. I had to develop new skills and devote hours to collating it all. I began to wonder what kind of person I might have to become, in order to create this history! For once, the amount of rest demanded by my illness (see earlier blog) worked in my favour. I spent weeks transcribing the documents into MS Excel, so I could analyse the data. That way I could take an overview of any aspect, according to the story I had to tell or a question I needed to answer.

Locations were an interesting challenge: many of the UXB records carried a map reference instead of a place-name. Without access to the relevant military map, I worked out a grid from the references I had and drew it onto my own Malta map, so I could locate the bombs. The activity reminded me of a skeleton crossword puzzle. When I did eventually find a copy of the real map, I wasn’t far off. Now I could plot the reported UXBs, link them to actual air raids and understand the implications for their surroundings. With map in hand, I set off to Malta to ‘walk the course’.

As I write this, even I am beginning to wonder at my own persistence. No wonder it took me three years to get to the first draft. It was worth it. I emerged from the intense activity with a robust body of information from which to construct the book. As well as providing the framework for the story, it meant I could give a much fuller description of the actions logged in the official reports, as well as linking events recounted by former members of REBD Malta with the likely date and location of the UXB concerned.

I wasn’t finished yet. Now that I was writing a book about bomb disposal, I had to learn how it was done.

A War Diary is a daily log of the main events of each relevant unit. The Diary of the Fortress Engineers, Malta, describes work done by the various subsidiary Companies, as well as air raids, casualties and damage to their headquarters. The Bomb Disposal (BD) Report for each week was attached as an appendix to the War Diary.

The first document I saw with the signature of 'Lt Geo D Carroll' as Bomb Disposal Officer was the BD Report for the week ending 10 May 1941. It listed the 59 unexploded bombs dealt with that week, with details for each one: serial number and date of the UXB report, the location, nationality, size and type of bomb (eg 50kg SD), whether it was on the surface or how deep it was buried. The final column logged the date the bomb was rendered harmless, with a brief description of the action taken.

It was only then that the enormity of what I'd uncovered began to sink in. As I read page after page describing what had actually gone on compared to what I’d found in books, I realised that the ‘booklet’ I'd planned to write couldn't possibly do the story justice. I began to contemplate writing my first book.

I had unearthed a goldmine: detailed, day to day account of the actions of RE Bomb Disposal in Malta from 1940 to 1944, and of the environment they worked in. More than a thousand pages of information revealed endless air raids, and the resulting thousands of unexploded bombs that were dealt with. Thanks to the National Archives, I was allowed to take copies of the documents, so I could study them at home between return visits to collect more.

But now I had to work out what all this information could tell me; statistics and lists are meaningless without interpretation. I was used to handling research material in some detail but this was on a different scale altogether. I had to develop new skills and devote hours to collating it all. I began to wonder what kind of person I might have to become, in order to create this history! For once, the amount of rest demanded by my illness (see earlier blog) worked in my favour. I spent weeks transcribing the documents into MS Excel, so I could analyse the data. That way I could take an overview of any aspect, according to the story I had to tell or a question I needed to answer.

Locations were an interesting challenge: many of the UXB records carried a map reference instead of a place-name. Without access to the relevant military map, I worked out a grid from the references I had and drew it onto my own Malta map, so I could locate the bombs. The activity reminded me of a skeleton crossword puzzle. When I did eventually find a copy of the real map, I wasn’t far off. Now I could plot the reported UXBs, link them to actual air raids and understand the implications for their surroundings. With map in hand, I set off to Malta to ‘walk the course’.

As I write this, even I am beginning to wonder at my own persistence. No wonder it took me three years to get to the first draft. It was worth it. I emerged from the intense activity with a robust body of information from which to construct the book. As well as providing the framework for the story, it meant I could give a much fuller description of the actions logged in the official reports, as well as linking events recounted by former members of REBD Malta with the likely date and location of the UXB concerned.

I wasn’t finished yet. Now that I was writing a book about bomb disposal, I had to learn how it was done.

Monday 15 March 2010

National Archives: finding that document

Today I helped someone on a World War 2 forum seeking information on the deaths of five infantrymen in Malta in March 1942. I was glad to – because not so long ago that could have been me.

The path which led me to an original 1941 document and the key to a mystery (see blogs2 and 4 March 2010) - was not a smooth one. It had taken that age-old combination of determination and luck. What I learned on the way could help you have an easier journey.

First step in researching personal history is to collect as much information from the individual or family as possible. Record them speaking if you can: it was replaying the actual words of Lt Carroll that gave me the essential clue I’d missed. Apply for the Army Service Record (from the Army Personnel Centre). You’ll need proof of next of kin if the service person is not applying himself.

Lt G D Carroll’s record shows he served in the Bomb Disposal (BD) Section in Malta in 1941-2. Now I wanted documentary evidence of what he did. My first attempt at using the National Archive in 2005 was unsuccessful. I got no results from the catalogue when I searched for BD Sections in Malta. The abbreviations they use do vary and it can be hard to pick the right one (there is a list available online which helps).

I needed help. Through the RE Bomb Disposal Officers Club, I contacted specialist historians, only to be told that no documents survived: they’d been destroyed in a fire, or lost in storage. I was on the point of giving up when, over dinner one evening, two friends gave me advice: a civil servant working for the Army said, “If it involves the Army, and it doesn't make sense, try assuming it’s a cock-up”. The other, a World War 1 historian, said: “There had to be a War Diary; it was compulsory. You just have to find it – and it may not be filed [in the National Archive] where you expect it to be.”

With their tips in mind, I went back to the National Archive website. Setting aside all assumptions about what a document would be called, or where it would be filed, I started again from scratch. The Catalogue Research Guides are a helpful starting point: in this case, listed as British Army Campaign Records 1939-1945, Second World War. Here you’ll find the Catalogue Reference for documents including Headquarters Papers, Unit War Diaries, War Office Directorate papers and Orders of Battle.

Next you need to establish which ‘theatre of war’. This is when my historian’s friend’s words echoed in my head. Malta is in the ‘Central Med’, right? Or, as a tiny Island, it’s a Smaller Theatre’? Neither – and this is where a broader knowledge of the war comes in: Malta War Diaries come under the Middle East: Catalogue Reference WO 169. A click on the ‘Browse from Here’ button takes you to a list showing the years covered and the piece reference numbers (from WO 169/1 to 24939). Once you get an idea of what’s where, you can jump forward to a document from the right period and browse from there.

I was unlucky. None of the Bomb Disposal Section War Diaries were from Malta: another dead end. Perhaps the files were really lost. I didn’t want to give up, but if I was going to find them I’d have to do it the hard way, and leave no stone unturned. If the War Diaries weren’t under Bomb Disposal Sections, where were they? Then I heard in my head the words of Lt Carroll: “I was attached to the Fortress Engineers.” If I could find their War Diary, it might help. I went through the lists again, and found some possible file references.

Two days later, on 5 September 2006, a year after my first visit to Malta with Lt Carroll, I sat in the National Archives staring at his signature on the Bomb Disposal Report for the week ending 10 May 1941 – attached as an appendix to the weekly War Diary of the Fortress Engineers. I was on my way.

The path which led me to an original 1941 document and the key to a mystery (see blogs2 and 4 March 2010) - was not a smooth one. It had taken that age-old combination of determination and luck. What I learned on the way could help you have an easier journey.

First step in researching personal history is to collect as much information from the individual or family as possible. Record them speaking if you can: it was replaying the actual words of Lt Carroll that gave me the essential clue I’d missed. Apply for the Army Service Record (from the Army Personnel Centre). You’ll need proof of next of kin if the service person is not applying himself.

Lt G D Carroll’s record shows he served in the Bomb Disposal (BD) Section in Malta in 1941-2. Now I wanted documentary evidence of what he did. My first attempt at using the National Archive in 2005 was unsuccessful. I got no results from the catalogue when I searched for BD Sections in Malta. The abbreviations they use do vary and it can be hard to pick the right one (there is a list available online which helps).

I needed help. Through the RE Bomb Disposal Officers Club, I contacted specialist historians, only to be told that no documents survived: they’d been destroyed in a fire, or lost in storage. I was on the point of giving up when, over dinner one evening, two friends gave me advice: a civil servant working for the Army said, “If it involves the Army, and it doesn't make sense, try assuming it’s a cock-up”. The other, a World War 1 historian, said: “There had to be a War Diary; it was compulsory. You just have to find it – and it may not be filed [in the National Archive] where you expect it to be.”

With their tips in mind, I went back to the National Archive website. Setting aside all assumptions about what a document would be called, or where it would be filed, I started again from scratch. The Catalogue Research Guides are a helpful starting point: in this case, listed as British Army Campaign Records 1939-1945, Second World War. Here you’ll find the Catalogue Reference for documents including Headquarters Papers, Unit War Diaries, War Office Directorate papers and Orders of Battle.

Next you need to establish which ‘theatre of war’. This is when my historian’s friend’s words echoed in my head. Malta is in the ‘Central Med’, right? Or, as a tiny Island, it’s a Smaller Theatre’? Neither – and this is where a broader knowledge of the war comes in: Malta War Diaries come under the Middle East: Catalogue Reference WO 169. A click on the ‘Browse from Here’ button takes you to a list showing the years covered and the piece reference numbers (from WO 169/1 to 24939). Once you get an idea of what’s where, you can jump forward to a document from the right period and browse from there.

I was unlucky. None of the Bomb Disposal Section War Diaries were from Malta: another dead end. Perhaps the files were really lost. I didn’t want to give up, but if I was going to find them I’d have to do it the hard way, and leave no stone unturned. If the War Diaries weren’t under Bomb Disposal Sections, where were they? Then I heard in my head the words of Lt Carroll: “I was attached to the Fortress Engineers.” If I could find their War Diary, it might help. I went through the lists again, and found some possible file references.

Two days later, on 5 September 2006, a year after my first visit to Malta with Lt Carroll, I sat in the National Archives staring at his signature on the Bomb Disposal Report for the week ending 10 May 1941 – attached as an appendix to the weekly War Diary of the Fortress Engineers. I was on my way.

Wednesday 10 March 2010

Hurt Locker hero: would he cut it in World War 2?

How would Hurt Locker hero, US Army Sergeant First Class Will James, have faired in the early days of bomb disposal back in World War 2? Former Royal Engineers Bomb Disposal Officer George Carroll, who was responsible for the disposal of over 1500 unexploded bombs between 1940 and 1944, has been surprised at how the job is represented in the action-packed Oscar-winning film.

The reason for James’ posting to Iraq is at least familiar: in 1940 many Bomb Disposal (BD) officers were co-opted to replace a dead man, as life expectancy in the first months of the blitz fell to a matter of weeks. But SFC James soon reveals personal qualities at odds with those traditionally demanded for bomb disposal. He flaunts safety procedures, refusing to send in a robot first to check a terrorist bomb, and removing his safety suit ‘for comfort’.

Such a man would have been considered unsuitable for the job in 1940, when self-discipline was considered essential and thrill-seekers were seen as a liability. For Lt Carroll, while protection of civilians or a military installation was the objective, his prime duty was to preserve his own life and those of his men – so they lived to tackle the next bomb. Bomb disposal specialists are always in short supply in theatres of war – whether on the remote Island of Malta in 1942, or in Iraq and Afghanistan today.

Perhaps there’s a clue to James’ behaviour in the 873 bombs he has defuzed. According to George Carroll, a bomb disposal officer progresses through three stages: first, concern through lack of knowledge, then using knowledge gained from experience. The third stage – long immunity from accident – can produce a fatal attitude to risk. George’s own moment came after working through five months of the London blitz, when a fuze he was examining in the workshop fired, taking off part of his thumb. Ironically, the event probably saved his life, reinforcing a proper respect for the explosives he subsequently faced.

So what is more dangerous – fear, or a lack of it? When Hurt Locker junior officer Eldridge admits to having been scared, James suggests that makes him a coward. George Carroll disagrees: “A truly courageous man is afraid, but carries out his duty anyway.” He describes his own feelings when approaching a live bomb as ‘concern’. While we agree with the film’s trailer that “you have to be brave”, that’s not a word George would use: he believes his job required less courage than an infantryman charging into enemy fire. The battle for the bomb disposal man is a psychological one: the pressure not just to appear calm, but to be calm, calculating and logical, and carry that through into action, when elsewhere in your brain there’s a natural and proper fear reaction.

It’s this critical balance between our perception of the danger and the controlled reality of bomb disposal that challenges any movie maker or writer dealing with the subject. How do you awaken in the audience the tension and courage of the ‘longest walk’ to a live bomb which could explode at any moment, without at the same time glorifying the act? The film’s creator has chosen to maximise the dramatic action, sometimes at the expense of reality.

The bomb disposal men I interviewed for my book, UXB Malta, would not thank you for presenting them as heroes. But they share one important feeling with the characters in the Hurt Locker: the immense satisfaction from saving lives, and from defeating the bomb maker. And as one leading modern Explosive Ordnance Disposal expert acknowledges, the movie represents “the intensity and courage displayed by EOD techs. What it takes to find, identify and then render safe those bombs – that’s a story, and it’s an incredible story.”

The reason for James’ posting to Iraq is at least familiar: in 1940 many Bomb Disposal (BD) officers were co-opted to replace a dead man, as life expectancy in the first months of the blitz fell to a matter of weeks. But SFC James soon reveals personal qualities at odds with those traditionally demanded for bomb disposal. He flaunts safety procedures, refusing to send in a robot first to check a terrorist bomb, and removing his safety suit ‘for comfort’.

Such a man would have been considered unsuitable for the job in 1940, when self-discipline was considered essential and thrill-seekers were seen as a liability. For Lt Carroll, while protection of civilians or a military installation was the objective, his prime duty was to preserve his own life and those of his men – so they lived to tackle the next bomb. Bomb disposal specialists are always in short supply in theatres of war – whether on the remote Island of Malta in 1942, or in Iraq and Afghanistan today.

Perhaps there’s a clue to James’ behaviour in the 873 bombs he has defuzed. According to George Carroll, a bomb disposal officer progresses through three stages: first, concern through lack of knowledge, then using knowledge gained from experience. The third stage – long immunity from accident – can produce a fatal attitude to risk. George’s own moment came after working through five months of the London blitz, when a fuze he was examining in the workshop fired, taking off part of his thumb. Ironically, the event probably saved his life, reinforcing a proper respect for the explosives he subsequently faced.

So what is more dangerous – fear, or a lack of it? When Hurt Locker junior officer Eldridge admits to having been scared, James suggests that makes him a coward. George Carroll disagrees: “A truly courageous man is afraid, but carries out his duty anyway.” He describes his own feelings when approaching a live bomb as ‘concern’. While we agree with the film’s trailer that “you have to be brave”, that’s not a word George would use: he believes his job required less courage than an infantryman charging into enemy fire. The battle for the bomb disposal man is a psychological one: the pressure not just to appear calm, but to be calm, calculating and logical, and carry that through into action, when elsewhere in your brain there’s a natural and proper fear reaction.

It’s this critical balance between our perception of the danger and the controlled reality of bomb disposal that challenges any movie maker or writer dealing with the subject. How do you awaken in the audience the tension and courage of the ‘longest walk’ to a live bomb which could explode at any moment, without at the same time glorifying the act? The film’s creator has chosen to maximise the dramatic action, sometimes at the expense of reality.

The bomb disposal men I interviewed for my book, UXB Malta, would not thank you for presenting them as heroes. But they share one important feeling with the characters in the Hurt Locker: the immense satisfaction from saving lives, and from defeating the bomb maker. And as one leading modern Explosive Ordnance Disposal expert acknowledges, the movie represents “the intensity and courage displayed by EOD techs. What it takes to find, identify and then render safe those bombs – that’s a story, and it’s an incredible story.”

Thursday 4 March 2010

Bomb disposal: rewriting history

As I stared at an email back in 2005 suggesting that Lt Carroll’s war memories of bomb disposal in Malta were imagined, I had to suppress some indignation on his behalf, and focus on the writer’s reality. Why would he doubt someone who talked so extensively, animatedly and in such detail about events nearly 65 years before? As we exchanged messages, it seemed the writer believed he ‘knew’ the facts from what had already been written about Malta – and Lt Carroll’s version just didn’t fit.

I like a challenge: I just had to find out what lay behind this conundrum. It wasn’t going to be easy. I soon learned that there are no lists of who served where in World War 2 to look at. A friend suggested a comprehensive book on bomb disposal in World War II – ‘Designed to Kill’ by Major A Hogben. It had a chapter on Malta, and sure enough only two BD Officers were named during the period of Lt Carroll’s service – and he wasn’t one of them.

Then a visit to the Royal Engineers Library turned up a hand-typed document outlining the history of 24 Fortress Company, RE in Malta, including the wartime bomb disposal unit. The information matched with Hogben’s book. Could this be his source? A telephone call to Major Hogben confirmed it. The last piece of information in the library document was dated 1982. How much detail would be remembered accurately so long after the war?

I decided to try the National Archives. My idea was to write some sort of booklet giving the correct information about who served in Royal Engineers Bomb Disposal in Malta which I could submit to the RE Library and circulate to interested parties – including my Malta doubter, of course!

At this point fate intervened. I was struck down with post-viral fatigue syndrome (aka ME) and spent much of the following months in bed. The most I could do was read, so I did: every book I could find about World War 2 in Malta. I found little or no mention of bomb disposal but I did discover the sheer scale of the bombing. I began to ask myself: what it must have been like to be a bomb disposal officer in those conditions?

My search for the answer began as soon as I was well enough to get out and about. It gave me a rewarding intellectual challenge which helped with my recovery, but also sleepless nights (see future blogs) as it revealed the extraordinary scale of RE Bomb Disposal in Malta during the siege.

I’ve been aware from the start that, once my own book is in print, it‘s open to the same scrutiny by future researchers and historians. I’ve used original ‘primary source’ documents from World War 2, but the story is inevitably my own interpretation of them. Those of us who set out to write about the past can only work with the best information we have and use our own knowledge and judgement to represent it as faithfully as we can.

I like a challenge: I just had to find out what lay behind this conundrum. It wasn’t going to be easy. I soon learned that there are no lists of who served where in World War 2 to look at. A friend suggested a comprehensive book on bomb disposal in World War II – ‘Designed to Kill’ by Major A Hogben. It had a chapter on Malta, and sure enough only two BD Officers were named during the period of Lt Carroll’s service – and he wasn’t one of them.

Then a visit to the Royal Engineers Library turned up a hand-typed document outlining the history of 24 Fortress Company, RE in Malta, including the wartime bomb disposal unit. The information matched with Hogben’s book. Could this be his source? A telephone call to Major Hogben confirmed it. The last piece of information in the library document was dated 1982. How much detail would be remembered accurately so long after the war?

I decided to try the National Archives. My idea was to write some sort of booklet giving the correct information about who served in Royal Engineers Bomb Disposal in Malta which I could submit to the RE Library and circulate to interested parties – including my Malta doubter, of course!

At this point fate intervened. I was struck down with post-viral fatigue syndrome (aka ME) and spent much of the following months in bed. The most I could do was read, so I did: every book I could find about World War 2 in Malta. I found little or no mention of bomb disposal but I did discover the sheer scale of the bombing. I began to ask myself: what it must have been like to be a bomb disposal officer in those conditions?

My search for the answer began as soon as I was well enough to get out and about. It gave me a rewarding intellectual challenge which helped with my recovery, but also sleepless nights (see future blogs) as it revealed the extraordinary scale of RE Bomb Disposal in Malta during the siege.

I’ve been aware from the start that, once my own book is in print, it‘s open to the same scrutiny by future researchers and historians. I’ve used original ‘primary source’ documents from World War 2, but the story is inevitably my own interpretation of them. Those of us who set out to write about the past can only work with the best information we have and use our own knowledge and judgement to represent it as faithfully as we can.

Tuesday 2 March 2010

Bomb disposal: journey into fear

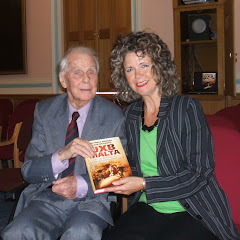

Five years ago all I knew about bomb disposal (BD), or Malta in World War 2, came from a few anecdotes told by former Royal Engineers BD Officer Lt G D Carroll, and some faded memories of the seventies TV series, Danger UXB. My visit to Malta in 2005 with Lt Carroll, courtesy of the Heroes Return Scheme, was to start an incredible journey of discovery that has led to UXB Malta.

Then aged 87, George Carroll was interviewed for over two hours by a local historical organisation. He related experiences from over a year as BD Officer for Malta, including the four months of the heaviest bombardment. His memories were patchy (more of that later) and occasionally confused. When we returned home, the interviewer wrote to express doubts about Lt Carroll's service in Malta, saying his name did not appear on any 'list'.

Knowing from his Army Service Record that his tale was authentic, I was intrigued, so I decided to investigate. My experience showed me how one single document, if not carefully assessed, can set history off on a wrong course. In this case, written from memory, a 'history' of a RE Company in Malta named only two Bomb Disposal Officers during World War 2: the 'list'.

After months of searching, I opened a file in the National Archives at Kew and found myself staring at the original signature of Lt G D Carroll from April 1941 in Malta. My real journey had begun.

Then aged 87, George Carroll was interviewed for over two hours by a local historical organisation. He related experiences from over a year as BD Officer for Malta, including the four months of the heaviest bombardment. His memories were patchy (more of that later) and occasionally confused. When we returned home, the interviewer wrote to express doubts about Lt Carroll's service in Malta, saying his name did not appear on any 'list'.

Knowing from his Army Service Record that his tale was authentic, I was intrigued, so I decided to investigate. My experience showed me how one single document, if not carefully assessed, can set history off on a wrong course. In this case, written from memory, a 'history' of a RE Company in Malta named only two Bomb Disposal Officers during World War 2: the 'list'.

After months of searching, I opened a file in the National Archives at Kew and found myself staring at the original signature of Lt G D Carroll from April 1941 in Malta. My real journey had begun.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)